Saturday Morning - Heading out

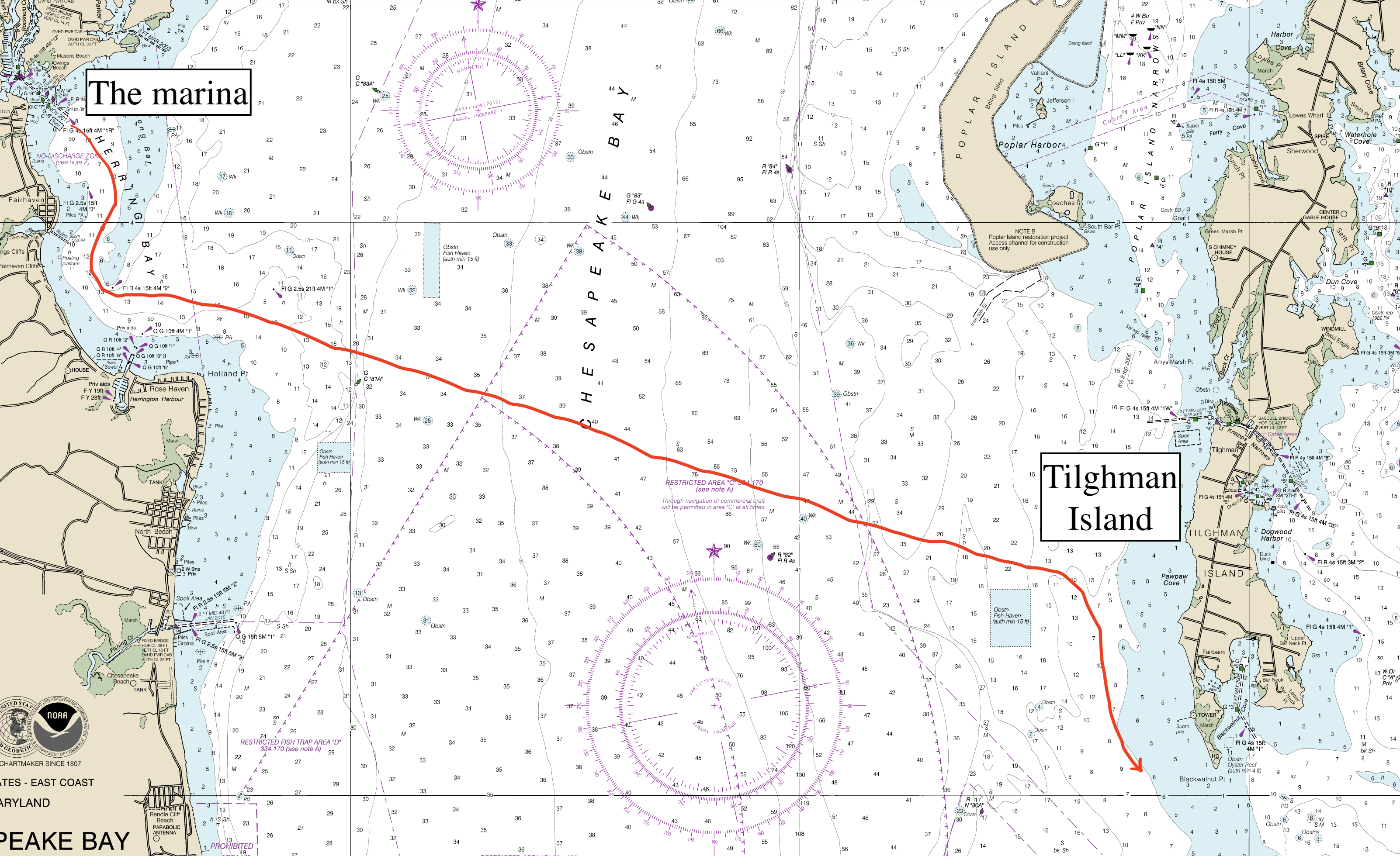

So it was decided, Jacob and I would probably never sail to Annapolis at this point, but that is O.K., because here we are now, leaving our home port of Herring Bay under sail power and heading east across the Chesapeake Bay, in the direction of St. Michaels, one of the most popular cruising destinations in the area.

Most people sailing to St. Michaels arrive on the north side of town, via the Miles River. This is because the northern shores of St. Michaels feature several nice marinas, as well as the historical Chesapeake Maritime Museum. The wind, however, is preventing us from taking this route.

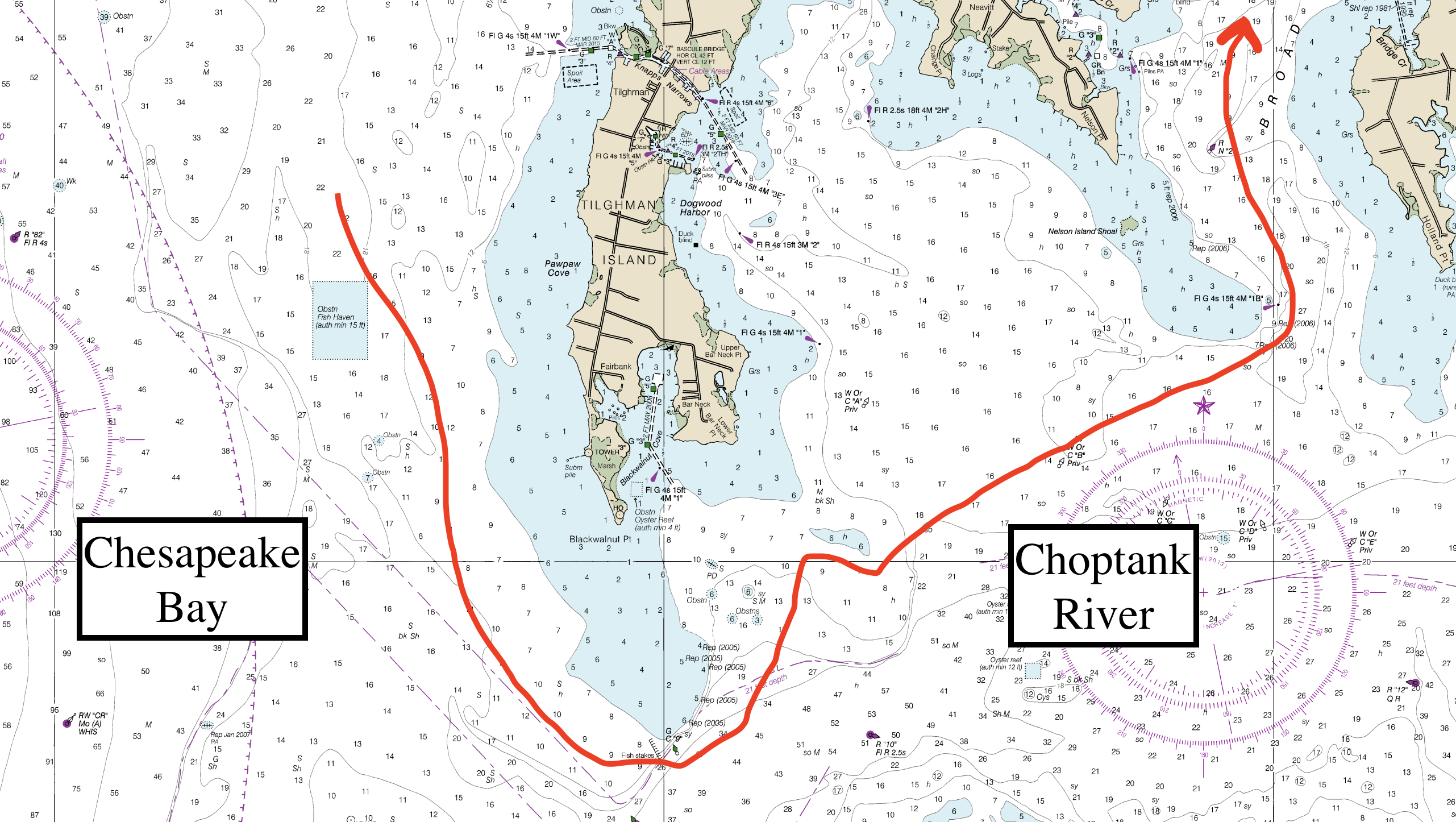

The wind is blowing primarily out of the east, but has a slight northerly component to it, making the northeasterly trek from Herring Bay to the Miles River impossible to do under sail power. Why do I say that the wind has a “northerly component” to it, rather than saying it is coming out of the northeast? Well, I don’t really know. You just have to trust me on this one. This is how people talk about it, and it makes sense from the sailboat perspective. Maybe it's because of the amount of vector-based thinking you are forced to do in the world of water-wind-propulsion, or maybe it's because saying that the wind is coming out of the “eastnorth,” which feels more true, just doesn’t sound right. But in any case, the northerly route to St. Michaels is off the table, so we head southeast, planning to round the bottom tip of Tilghman Island, enter the waters of the Choptank River, and then turn north to find Broad Creek, the anchorage spot that Chris had mentioned earlier that morning.

Jacob and I both started sailing in July, so we don’t have that much on-the-water experience yet. But despite this lack, I have learned how to do some personal seasickness calculations. As we are just leaving our little bay and entering the open, exposed waters of the actual Chesapeake, I do some quick mental math: 10-15 knots of steady wind, gusting into the mid-twenties, sailing essentially upwind for the entire route… “Take the helm for a second,” I say to Jacob and climb through the companionway hatch and turn to descend into the cabin, “I’m going to find my Dramamine.”

Seasickness and I are actually new acquaintances, having just met on my recent voyage across the Baltic and North Seas. When we left the port in Stockholm, I was naïve, and even though I had been convinced to buy some seasickness tablets before departing, I thought that I would probably not need to use them. Even though I’m susceptible to motion sickness when I ride in the back seat of a car, especially on windy or hilly terrain, I somehow thought that I might be immune to seasickness. I think I just wanted so badly for this to be the case, my mind full of literary images of the great men of the sea, that, while the rest of the crew were applying patches and popping pills, I stubbornly refused medication. The idea of Captain Ahab popping a few 50mg Dimenhydrinate tablets out of a foil wrapper before leaving port seemed ridiculous to me. But oh, did I learn quickly the folly of my ways! Ten days later, when we finally arrived in England, I rinsed my mouth with about a gallon of mouthwash and vowed that I would never sail upwind unmedicated again.

Emerging back up from the cabin, I remove two little white pills from a tube and swallow them. Sure, we’re on the Chesapeake, where the waves aren’t likely to get much bigger than a few feet. But remembering those excruciating days and nights spent on the North Sea, and how I spent so much of my time alternating between cowering in my bunk and leaning over the railing on the low side, I decide that I’m not going to take any chances. I offer the tube to Jacob. “No thanks,” he replies, “I want to see how I do without them.” Ah, a familiar tune. “Suit yourself,” I say, and put the tube in my pocket, for easy access.

Saturday Afternoon - Rounding Tilghman Island

An hour later, we’re already almost halfway across the bay. The winds are gusting, but we have our full sails up, opting for speed over comfort. We have never really anchored before and want to make sure that we arrive at the anchorage with enough daylight to spare. We’re doing about 6 knots of speed (about 7 miles per hour—yes, sailboats are slow), which is about as fast as my boat will go. I’m at the helm, my eyes watery from the wind but focused on the horizon, my legs positioned to provide balance given the extreme heel of the boat, my one hand controlling the wheel and my other resting in what I hope is a comforting and not a condescending way on the back of poor Jacob, who is leaning over the side of the boat and getting a second taste of the oatmeal I had made him that morning. Once he’s back upright, I wordlessly remove the Dramamine from my pocket and slide it into his hand. We all learn somehow.

After another hour or so of speeding across the bay, we start looking at the chart in greater detail and realize that we need to head much further south than we had thought. Even though it visually seems that we are on course to clear the southern end of Tilghman Island, the chart reveals a shallow section that extends even further south that we would do best to avoid. I turn the wheel and adjust our course to head just shy of due south, bringing the wind almost across our beam.

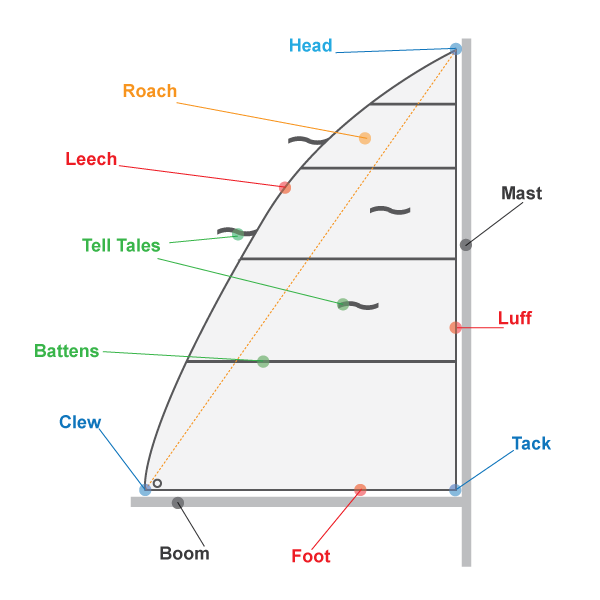

“Let out the main sheet,” I instruct to Jacob, who is at this point back to health and trimming the sails. I look expectantly at the boom, which should move farther away from the center of the boat as Jacob introduces slack to the system of ropes and pulleys which adjusts the position of the boom. I wait a few seconds. It doesn’t move. “Let out the main sheet!” I repeat, frowning as I feel the boat slow down and start to dangerously heel over. With the boom still near the centerline of the boat, the wind, instead of splitting around the leading edge of the sail and flowing around it like a wing, creating lift and pulling the boat forward, is blowing right into the side of the sail. This buildup of lateral pressure, high and center on the boat, is pushing us sideways, and I begin to see flashing images of capsized boats before my eyes. “Let out the damned main sheet, Jacob!” I yell, glancing down from the sail and at my friend, standing haplessly in the cockpit with the main sheet in his hand, let almost all the way out.

“I am!” Jacob yells back, “but the boom isn’t moving! It must be stuck on something!” Panicked, I adjust our course back upwind, where the boat rights itself and speeds back up. We’re getting pretty close to the island shoal now, but I figure that we still have a few minutes before we’re in real danger. And besides, in the scheme of things that could go wrong, I’d rather run aground than capsize. We begin frantically searching for the culprit of the stuck boom. I stay at the helm while Jacob exits the cockpit and heads to the foredeck to check all of the lines.

“Find anything?” I yell somewhat impatiently as I watch the distance between our boat and the shallow water decrease on the chart plotter. “No, it looks like everything is fine up here,” Jacob yells back. “Jesus Christ,” I utter to myself, and nervously run both hands through my hair and tilt my head back slightly. That’s when I see it. Twelves inches above my head, almost right in front of my nose, I see what is causing the boom to stick in place. “Jacob, come back!” I yell. “I figured it out!” Jacob scrambles back into the cockpit and looks at me expectantly. “Well, what?” I don’t say anything, but merely tilt my head up a little bit. Jacob follows my gaze and then slaps his forehead with his palm. How could we have been so stupid. “Oh my god,” he exclaims, “we forgot to remove the topping lift.”

On our Pearson, the topping lift is a fixed wire with a quick release clasp on the end that hangs down from the backstays and connects at the very end of the boom. It is used to hold the boom up when the sail isn’t hoisted. This prevents the boom from falling into the cockpit and taking up space when you are at dock or motoring around with the sails down. We had forgotten to disconnect the wire when we hoisted the sails that morning, and I could tell that the wire was under a tremendous amount of load and was starting to fray. Luckily, the shackle that attaches the wire to the boom should be able to be easily disconnected by pulling out the quick release pin.

We bring the main sheet back in so that the boom doesn’t violently swing out once we release the topping lift and I begin pulling on the pin. We are sailing just off the wind but the force of the sails is so strong that the pressure on the boom, and therefore also on the wire’s connection point, won’t allow the pin to release. I switch positions with Jacob, take the helm again, and start pointing us dead upwind. The headsail starts flapping violently and the boom begins to bounce and shake from the luffing of the main sail. “Can you get it?” I ask, keeping both hands on the wheel, at pains to prevent us from accidentally crossing the wind and tacking the headsail to the wrong side. “No!” Jacob replies, “It’s stuck!” The pressure of sailing for several hours with the topping lift in place had bent the pin slightly, and the bouncing of the boom made it difficult to get any kind of purchase with our fingers on the small metal pin.

“Shit,” I think, “If only we had some kind of useful tool up here that we could use to pull this pin.” Then I remember: The macramé that Jacob bought from Quinn! In the list of potential uses he used to sell it to us, he even explicitly mentioned “releasing quick clasps.” Feeling relieved but also awkward at the idea of learning this important safety lesson from a ten-year-old, I reach my hand in my pocket and pull out Quinn’s handiwork. I feed the loop through the pin on the quick release, grab the latticework and pull. The pin instantly comes loose, the clasp releases, and the boom is free. We re-secure the topping lift, let out the main sheet, and adjust our course for the third time in about five minutes.

Saturday Afternoon - The Choptank

Sailing, especially in bulky, slow boats like mine, can feature a lot of downtime. Or at least large swaths of time where you are just staring at the horizon, plodding along at 7 miles per hour (if you’re lucky), monitoring the conditions around you, and waiting for something to happen. These large, empty periods are sometimes punctuated by smaller moments of high intensity and excitement, like our topping lift debacle. A problem presents itself, your heart rate goes up, you quickly assess possible solutions, weigh your options, pick one, implement it, and then deal with the consequences. This is what I like about sailing. If all goes well, if you make the right decision (or maybe I should say “a right decision,” as there is rarely one clear correct answer) this moment of stress and animation slowly tapers off and you slide back into another long period of appreciating the clouds, listening to the gulls, and wishing that you had purchased a faster boat.

But sometimes, and especially if you are novice, unprepared sailors on a 40-year old boat sailing upwind towards a spontaneously chosen destination that you have almost zero knowledge of, those little moments just keep coming, and coming.

Rrrrrrrrrrrrrippp!

As we round the bottom of Tilghman Island and begin to head northeast again, back upwind, we hear a slow, tearing sound on deck. It sounds like a deck of cards being shuffled together. Just as we had both begun to come down from the last hiccup and slowly sink into the pleasant morass of sailing-boredom, we are jolted to action once again. Modern sailing boats are made out of a variety of fun materials, all of which you get to become intimately familiar with in the process of sailing and maintaining your boat: wood, metal, fiberglass, hemp, polyester, and plastic. But there’s only one material that makes this distinctive ripping sound on board, so it doesn’t take us very long to suss out the source of this new problem. We immediately stand up and check the sails.

The foot of the mainsail is starting to rip, right at the clew. Dumbstruck at the sight of this misfortune, we both just stand there, arms limp at our sides, listening to the horrifying noise and watching as the rip widens. When we first lay eyes on it, it’s probably already six inches wide. We gape in slack-jawed disbelief and awe as the power of the wind stretches and snaps thousands and thousands of (expensive) little polyester fibers. Seven inches. Eight inches. Nine. I suddenly come to my senses and realize that if we don’t do something, the entire sail will rip free of the boom and we’ll have a lot of heavy canvas just flapping in the breeze. I lock the wheel, instruct Jacob to be ready to drop the main halyard, and scurry up to the mast. “Now!” I yell. Due to the urgency of the situation, I did not think we had time to point the boat back into the wind, so wrestling the sail down while it’s being filled by the wind is a struggle. But I notice that as soon as the tension in the main halyard is released and the sail billows out, no longer pulled taut along the luff, that the rip stops its spread.

Once the sail is down, we tie it up and have a strategy meeting in the cockpit. It’s about 3:00 p.m. already, and we’re more than halfway to the anchorage. Turning back now would mean that we would run out of sunlight and have to sail in the dark, and besides, what good would turning back do us anyway? It’s not like we’re going to be able to repair the sail ourselves anyway; wherever we end up going right now, we’re going to end up limping there. So our destination is decided, we will continue for the anchorage, where, hopefully, if we can find him, an eager Chris will be able to advise us.

This matter decided, it's on to the next issue: propulsion. It’s clear that we can’t put the full main sail back up, that would just do further damage to the sail and possibly get us into deeper trouble. Right now, we just have the headsail up; can we continue this way? I look down at the helm and note the position of the piece of tape that indicates the “top” of the wheel. When this piece of tape is high and center on the wheel, it means that the rudder is pointing straight ahead. Under headsail alone, the piece of tape is very far from its home, almost 200 degrees around the wheel. Because the headsail is attached to the boat at the foremost part of the bow, which is very far from the center, or “pivot point,” of the boat, the force exerted on the boat by the sail makes the boat want to turn. In order to counteract this turning force, the rudder needs to steer the back of the boat in the opposite direction. This means, in order to go straight, the rudder needs to be almost sideways, which causes a lot of drag in the water and slows the boat down. Not ideal. So unless we want to switch the motor on and motor-sail the rest of the way there, sailing with just the headsail doesn’t seem very appealing.

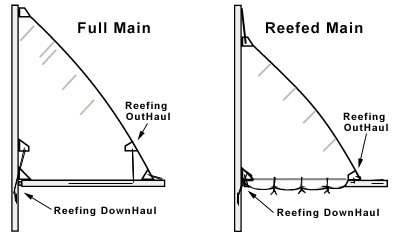

So where does that leave us? I look at the rip on the mainsail again and note that it’s right at the foot of the sail, well beneath where the first reef line is attached. This means that if we want to raise the sail partially, but stop at the first reef point, we could pull taut the reef line and in effect create a new foot for the sail, albeit with much less sail raised. This arrangement seems ideal. It will allow us to still have some main sail up, balancing the boat and adding to our propulsion, but without stressing and damaging the weak part of the sail.

We agree on this course of action, implement it, and wait for the consequences. The boat balances out, the tape on the helm returns to the upright position, the rip doesn’t appear to be widening anymore, and we are moving along again, on course, but now at about 4.5 knots, a tad slower than before, but an acceptable speed given our problems. For the next 30 minutes we monitor the situation closely, but then, as the efficacy and sagacity of our plan appears to prove out, we start to relax again.

Saturday Afternoon - The Choptank

We’re now on the other side of Tilghman Island and are officially in the waters of the Choptank River, although it really doesn’t feel any different than being on the bay itself, except that we are now near the Eastern Shore of Maryland, which features a slightly more nautical culture than the Western Shore. It's a windy Saturday afternoon, so there are many more sailboats around us now. You might think, as I used to, that given the huge expanse of open water available, people wouldn’t need to crowd around one another as much. And for powerboats, this is theoretically true (although they always seem to love putting themselves on collision courses with much less maneuverable sailboats…). But since sailboats are confined to the whims of the wind, and since certain points of sail are more favored in certain conditions than others, it often happens that a bunch of sailboats with similar destinations will end up lined up with one another. Also, it’s just kind of fun to “race” other boats, even when you are down a full main sail.

As we round the island and set a course for the entrance to Broad Creek, a few challengers emerge. One of these is a historic, hundred-and-60-foot-long, three-masted schooner ship that has about nine sails up. Needless to say, despite the almost century-long engineering gap between this 19th century schooner and my 1987 Pearson sloop, the schooner still has the upper hand. More sail and longer boat equals more speed. Sailing is, after all, more or less an ancient technology, and while we have fiberglass hulls and steel-cabled rigging now, the essentials are about the same as they always were.

But if it were an actual regatta, we wouldn’t be in the same racing class as the schooner anyway. Instead, our attention is brought to a much more fair fight when a sloop of a similar size to us with a deep blue hull appears on our port side. They had been in the line behind us for a while and were now planning to pass us. They come close enough that we are able to easily exchange the requisite howdy-there-captain waves, and I note that they are a group of three middle-aged men, beers in hand, clearly out for a Saturday afternoon pleasure cruise. “Ready on the jib sheet,” I say to Jacob, “I think we can smoke these guys.”

Now, I would love to write that, despite our reefed main sail, through sheer willpower and sailing acumen, Jacob and I were able to expertly trim the sails and gain enough speed to compete. I have this beautiful image in my head of our boat slowly inching up on them, their having been lulled into a false sense of security, and our catching them unawares as we suddenly pass. I remove my cap and wave gleefully as we overtake them. Gleaming grins on our faces and shocked looks on theirs, although their faces slowly soften into reluctant smiles and they raise their beer bottles in salute to our sailing prowess.

Would be nice. In reality, we stand no chance. I unnecessarily order Jacob to continuously make fine adjustments to our worn-out sails and we watch as the blue hulled boat, despite its crew being more focused on cutting limes than trimming lines, easily outpaces us. Still, it’s an enjoyable hour of playing at racing sailor, and since Jacob is doing most of the hard work of grinding winches and pulling lines, I’m having a great time. We certainly aren’t in racing condition, but our (Jacob's) hard work is mildly rewarded as we are able to eek out a bit more speed through careful trimming of the sail. This kind of micro-efficiency-optimization is another one of the joys of sailing. Nobody is raising a glass to us, but we are grinning anyway.

Suddenly, the blue boat violently tacks, putting us on a near collision course. “What the fuck is that?!” I yell, and we swerve to narrowly avoid hitting them. As we pass one another, the man at the helm raises a hand of apology while the other men point and gesture frantically in the direction of their previous—and our current—course. Jacob grabs the chart plotter and starts zooming in on the vector map. “Ah,” he says, “there’s another shallow shoal right ahead.” Sure enough, less than a quarter mile ahead of us is a clearly marked (if you are zoomed in enough on the chart plotter, that is!) little island of shallow water, about five feet at low-tide. “Let’s just go over it,” I suggest, knowing that one of the advantages of my little boat is its relatively shallow draft, coming in at just 3’ 9”. I have no idea where the tide is today, but we should probably clear it, right? Jacob, always the conservative and safety-minded of the two of us, thinks that we should just tack ourselves and go around it. After all, our chart plotter is almost 10 years old, and who knows what the shoal actually looks like today. But I’m still in racing mode. Buoyed by this sudden advantage, I want to charge ahead and secure victory.

We argue for another few minutes as the distance between us and the shoal steadily decreases. When we’re only a few hundred yards from its edge, I finally give in to Jacob’s prudence and prepare to tack. Quickly, Jacob hauls in the main sheet, releases the working jib sheet, and I bring the wheel hard over. The boat turns 120 degrees to starboard and I immediately realize the huge mistake we have made. “FUCK!” I yell, and grip the wheel tightly, unsure of what exactly to do. In our deliberations about what to do about the shoal, we had neglected to look at the line of sailboats behind us, and one of them, which had clearly been gearing up to pass us, was now only a few hundred yards away, on a direct collision course, and going FAST. Not having much room to work with, given the wind angle, I make the decision to just stay our new course, hope the other boat can swerve around us, and pray that they don’t yell at me for our dangerous and erratic maneuver.

Luckily, the other boat is able to quickly adjust their course and a collision is avoided. Once safety is assured, I avert my eyes and look straight ahead, too embarrassed to risk making any kind of visual or verbal contact with the crew of the boat that just witnessed one of my biggest and most dangerous sailing mistakes to-date. “Oh my god,” I hear Jacob say, “Look!” I don't want to, but I reluctantly turn my head towards the vessel, fully expecting to see angry grimaces and admonitory hand gestures. Instead, confusingly, I am greeted by eager smiles, shouts, and full, two-handed waves. I blink twice, trying to understand the sight before me. Then, I recognize the boat. Realizing what had just happened, a barb of embarrassment shooting through my body, I slap my palm over my eyes and suck-in air hard between my teeth.

“We did not just cut off Chris and his family in the middle of the Choptank, did we?” I ask Jacob. “Yes we did,” he says, and begins waving back, gesturing towards the shoal.

Saturday Evening - Arriving at St. Michaels

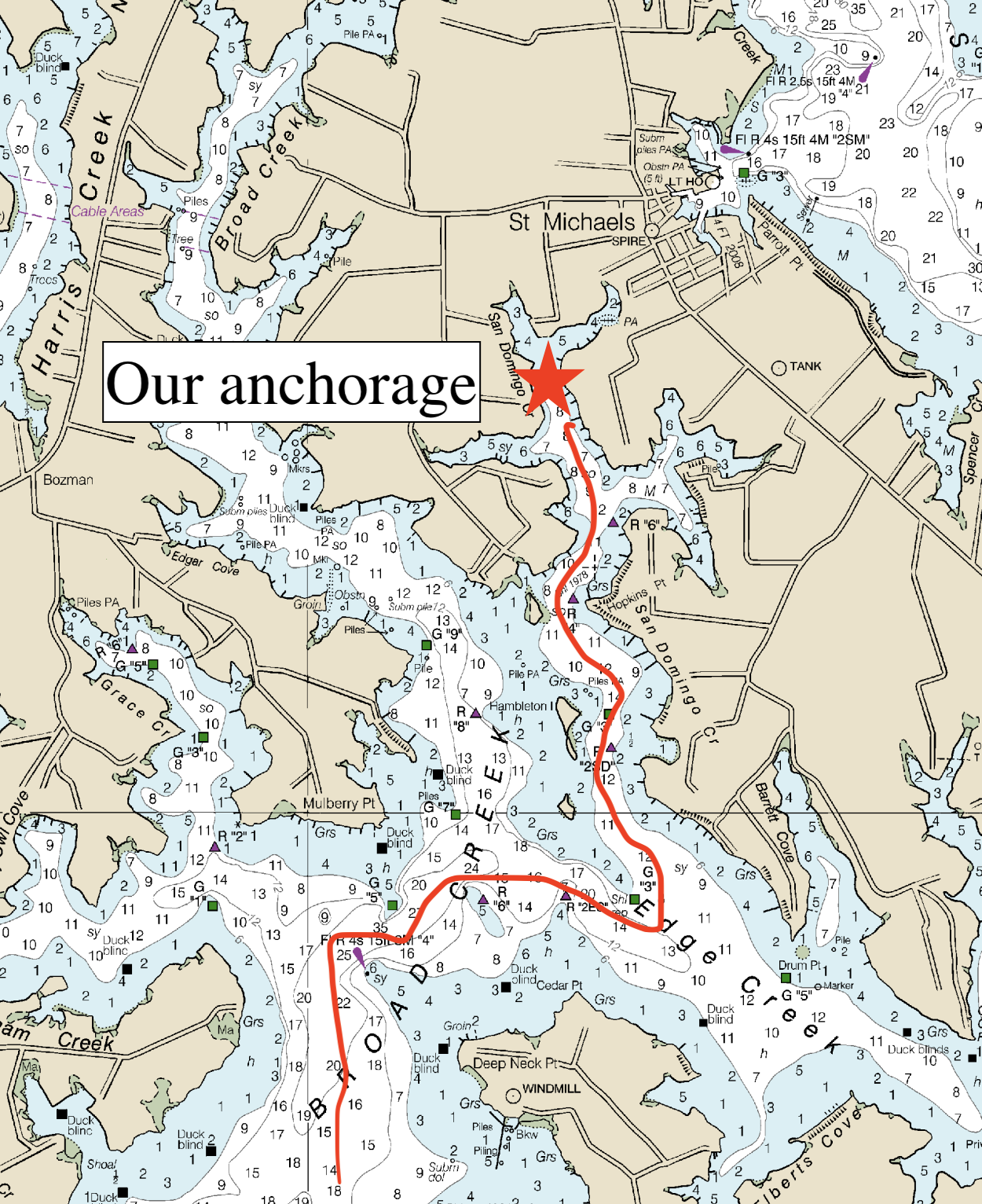

The next few hours are a bit of a blur for me. Chris and his family also tack to avoid the shoal, giving me some comfort that they, too, had not seen it on their chart plotter until we had pointed it out. Their boat is much faster than ours, and points into the wind better as well, so they quickly pass us and make for Broad Creek at a better angle. We do our best to follow them, as we don’t know exactly where we are planning to anchor, but this proves a difficult task given how much faster they are. As we enter Broad Creek, the surrounding land creates a wind shadow, and our speed is reduced even further. We eventually drop the headsail, turn on the motor, and motor-sail directly up the creek.

Having now lost sight of Chris’s boat, we decide to just motor as far up the creek as we can, using the little dot marked “St. Michaels” on our chart plotter as our guiding star. Worst case scenario, we just anchor somewhere that feels safe to us, and then we kayak the rest of the way into town, tie up at the dinghy dock, and find Chris and co on land.

Luckily, as we are motoring up the creek, we hear a familiar pre-pubescent voice hailing us on channel 16. “Liberty Call, Liberty Call, Liberty Call, this is Quinn. Where the heck are you guys? Please confirm and switch to channel seven-two. Over.” (Liberty Call is the name of my boat, inherited from the previous owner—I haven’t changed it yet.) We laugh at hearing our friend’s voice on the VHF and switch channels. Quinn, in his precocious way, walks us through exactly how to navigate the rest of the creek and locate their family in the anchorage. It’s starting to get dark, but it looks like we made it just in time. Right as the sun is beginning to set, we see our little cruising group—Chris and the other Pearson family—tucked away and anchored at the very top of the creek.

We pull in and wave at everybody. Quinn looks so happy to see us, clearly pleased with himself that he was able to convince us to come along. The Pearson family give us friendly, but slightly confused waves. They clearly didn’t know we were coming. I begin to wonder if Chris already told them about my stupid maneuver back in the Choptank. I start to feel self-conscious. This feeling is exacerbated when the initial relief of having finally arrived at our destination is replaced by the anxiety of the dawning realization that we are going to have to set an anchor. Jacob and I have set an anchor before, but only once, and certainly not with two hungry families expectantly waiting for us so that we can all go to dinner together. Pressure's on.

I stay at the helm and work the motor while Jacob goes to the foredeck and opens the anchor locker. We give each other a little look and nod across the entire length of the boat that says: “Are you ready? Let’s not fuck this up in front of our new friends.” I position myself between the two boats and motor forward, into the direction of the wind, to allow Jacob to drop the anchor. Splash I throw the engine in reverse and allow Jacob to pay out the anchor line, first the 20 feet or so of chain, and then… a bunch of rope? Shit. I suddenly realize that we forgot to actually measure how much anchor rode we have. Most people mark their rode every ten feet or so, that way they can know how much they are letting out. We had meant to do that this weekend but clearly had forgotten in all of the excitement. The water is only seven or eight feet deep, and the anchorage is so protected from the wind that I’m not worried, however. We’ll just let out enough that it looks good and call it a day.

Once Jacob is satisfied, he cleats off the line and motions to me that he's finished. I’m suddenly aware that everyone is watching us. I throw the boat in reverse and pull back on the anchor, looking at fixed landmarks around to see if we’re moving. One of the landmarks I use is the Pearson family’s boat, which, unfortunately, seems to be getting closer and closer. Shit, that means we’re dragging anchor. The already uneasy smiles on the Pearson family’s faces get a little tighter and a little flatter as our boat nears theirs. I throw the motor in neutral and motion to Jacob that we need to start over, and he begins pulling the anchor line back in. Feeling it neccesary to assuage their fears, I turn to the Pearson family and yell, in what I hope is a confident tone: “Don’t worry! I promise we won’t hit your boat!” Just the sentence everyone wants to hear from their anchorage neighbors. They nod to show me that they heard my words, but their body language tells me that they aren’t watching this whole anchor procedure out of idle curiosity, but rather as a means of self-defense and preservation. The husband seems on the verge of putting out an extra couple of fenders.

We motor forward and try the same technique again, with the same result. We come even closer to the other Pearson this time, and I begin to actually sweat. We motor forward once again, this time I choose to take advantage of our shallower draft and pull a little closer to the shore, hoping the ground might be a little firmer in a spot where other boats can't normally reach. Chris yells to us from his boat, trying to be helpful: “How much anchor rode do you have?” Why does he have to ask that? It’s clear that we have almost no idea what we’re doing, but do we really have to admit it verbally too? “Umm… a bunch!” I yell back to him. He smiles, gives a merciful nod of understanding, and busies himself with preparing his dinghy to head to town.

We try to anchor three more times. On the last attempt, the anchor seems to actually hold! I have the boat in reverse idle and we don’t appear to be moving. Jacob and I look at each other across the boat with giddy glances. We did it! We look over at Chris’s boat and he’s standing there, looking pleased as well. “Now throttle up one more time to make sure it really holds,” he offers, and I push the throttle lever forward. The boat kicks for a second and then slowly starts moving backwards. Sigh. Our anchor just doesn’t seem to want to set.

Chris’s whole family is already sitting in their dinghy, hungry, and ready to go to dinner. The Pearson family has already left for town in theirs, promising to find a restaurant and reserve a table. I don't know this for sure, but I think that they crossed themselves and said a prayer for their boat as they motored away. Jacob and I look at each other dejectedly and then over at Chris, who is scratching his head. “Hey, why don’t we just raft up?” he offers, politely, obviously sensitive to our sense of pride but probably also feeling the grumbles in his own stomach. He tells us that his anchor is strong enough to drown an elephant, or some other vaguely violent and folksy turn of phrase, and we immediately agree, eager to end this prolonged embarrassment. We pull the anchor in, swing the boat around, and tie it up to the side of his.

Ten minutes later, exhausted and famished, we are finally loaded up along with Chris’s family in their dinghy and motor the short distance from our boats to the city's little auxillary dock. The anchorage is in a quiet little backwater creek, and when we arrive in town, we realize that we absolutely made the right decision to come here today. Jacob, notably, does not fall in the water and embarrass us further as we dismount and start walking to the restaurant with our new friends.